Introduction

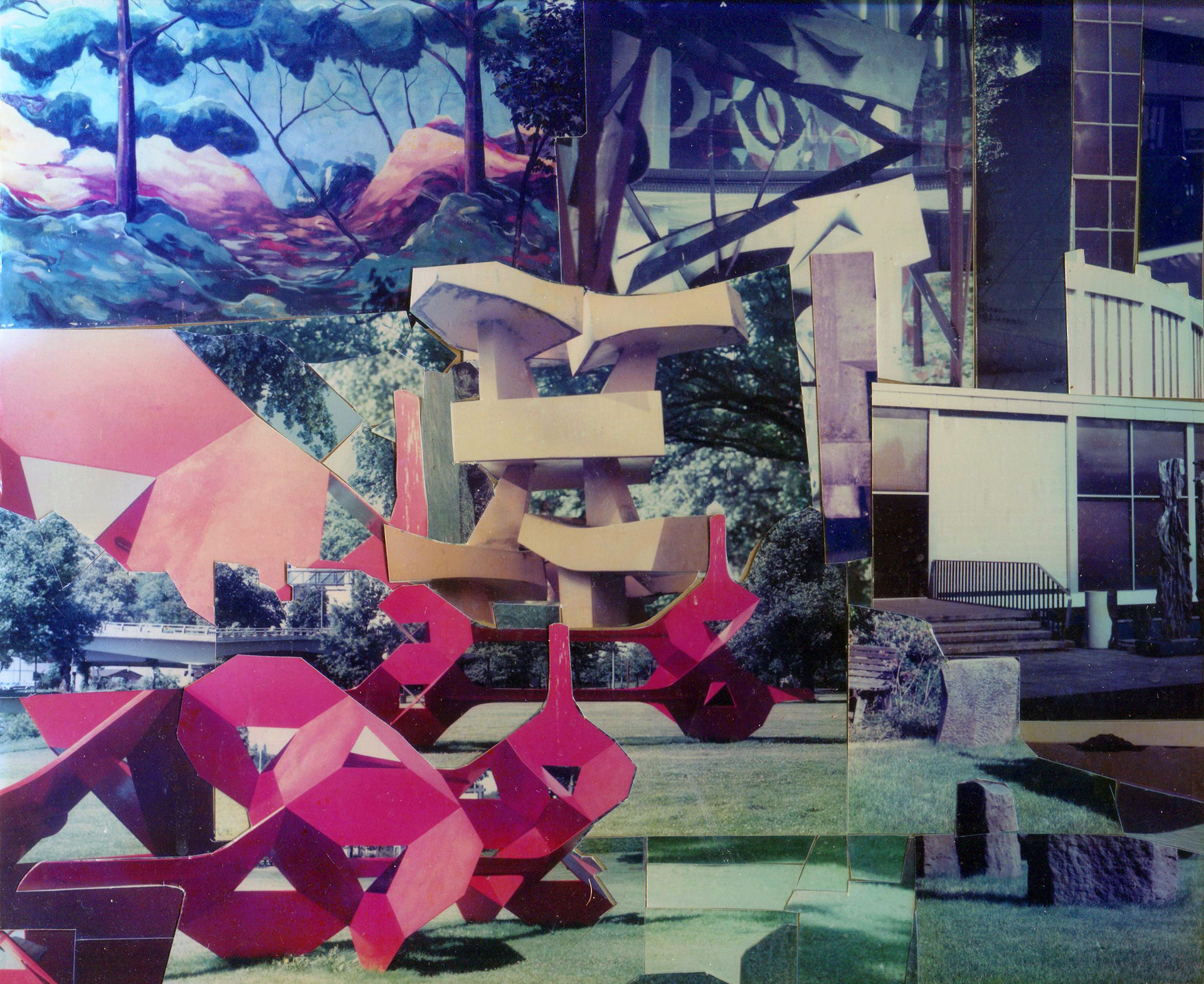

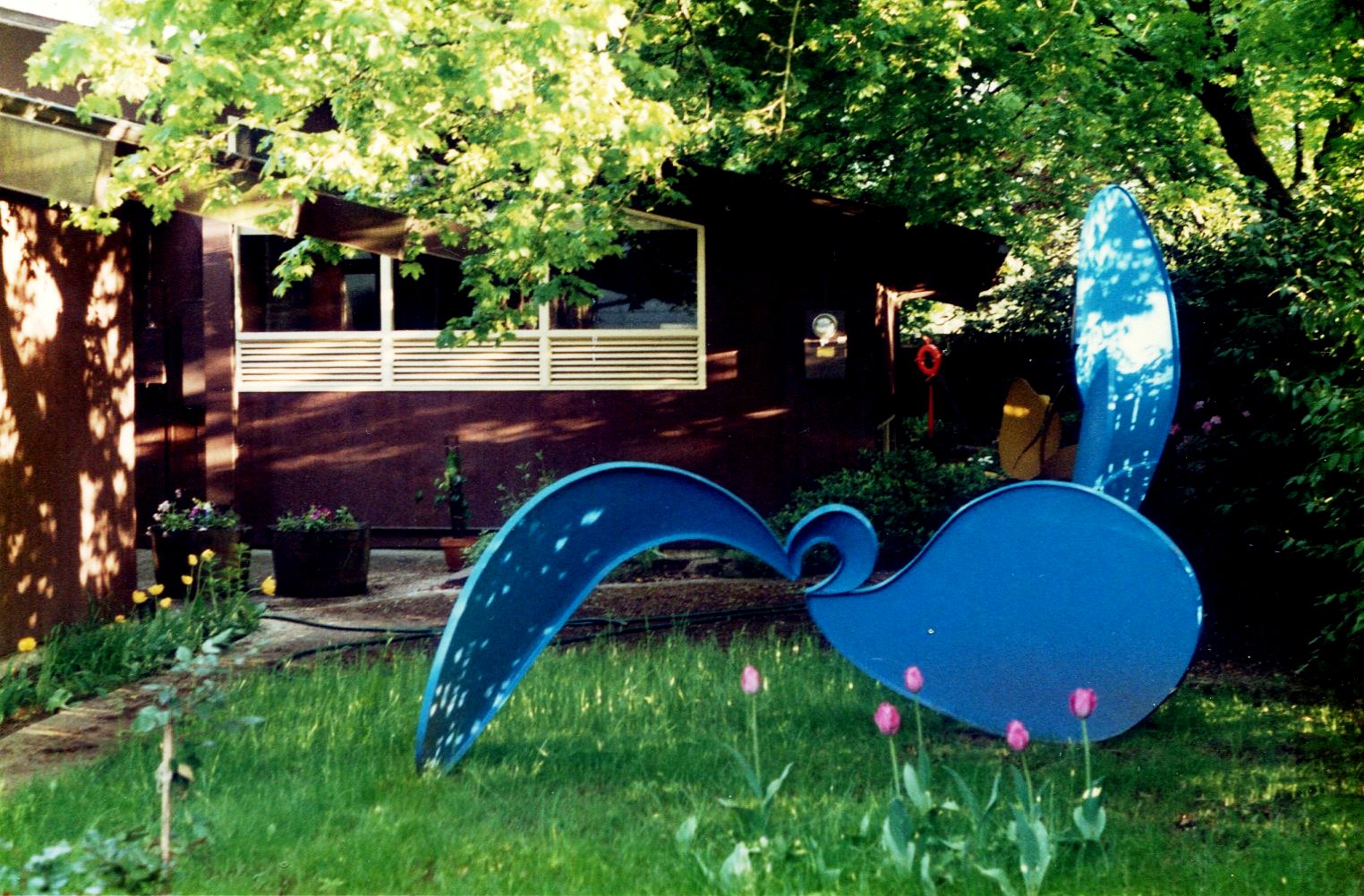

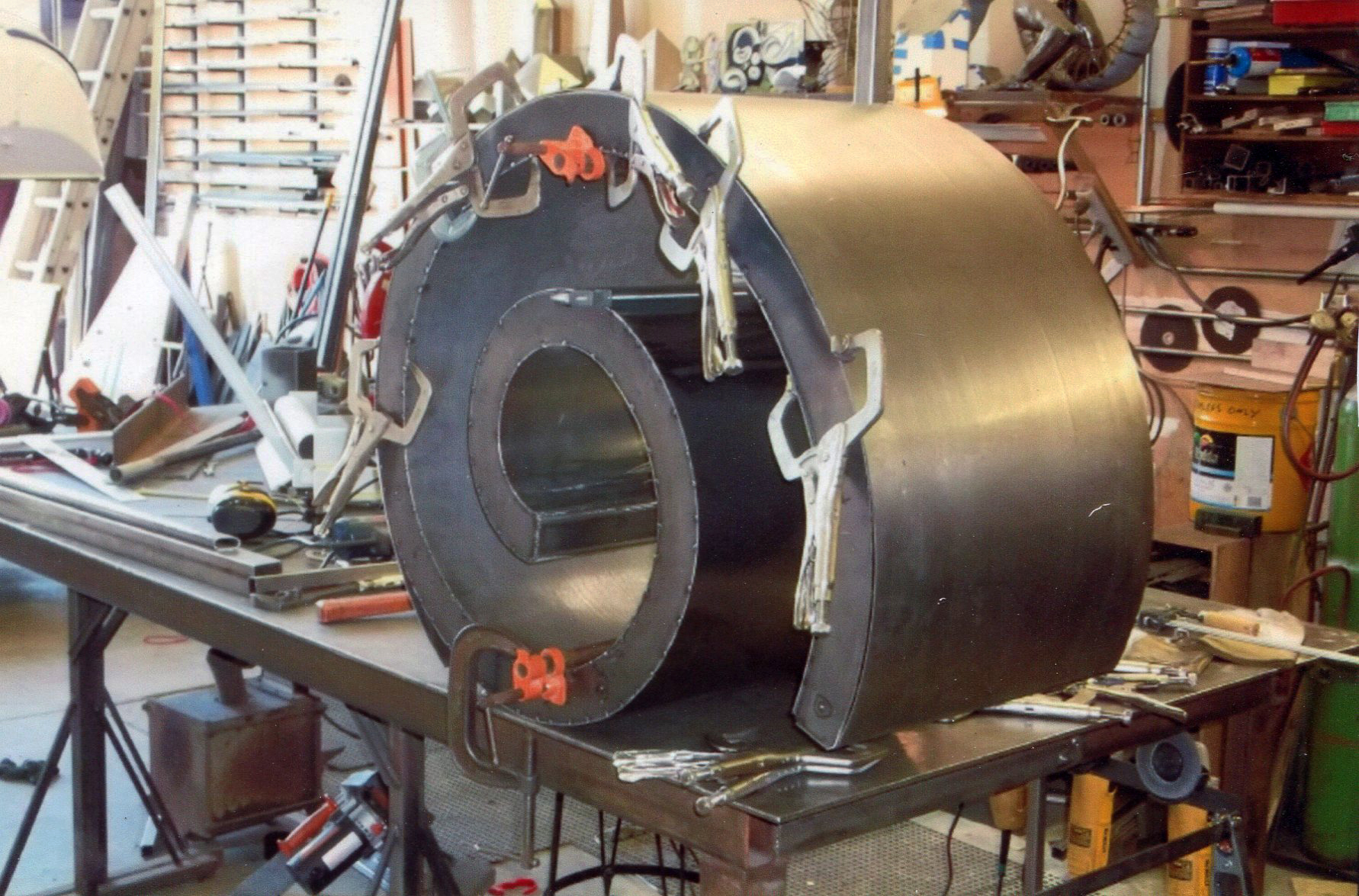

1a. View of sculpture garden through the east gate

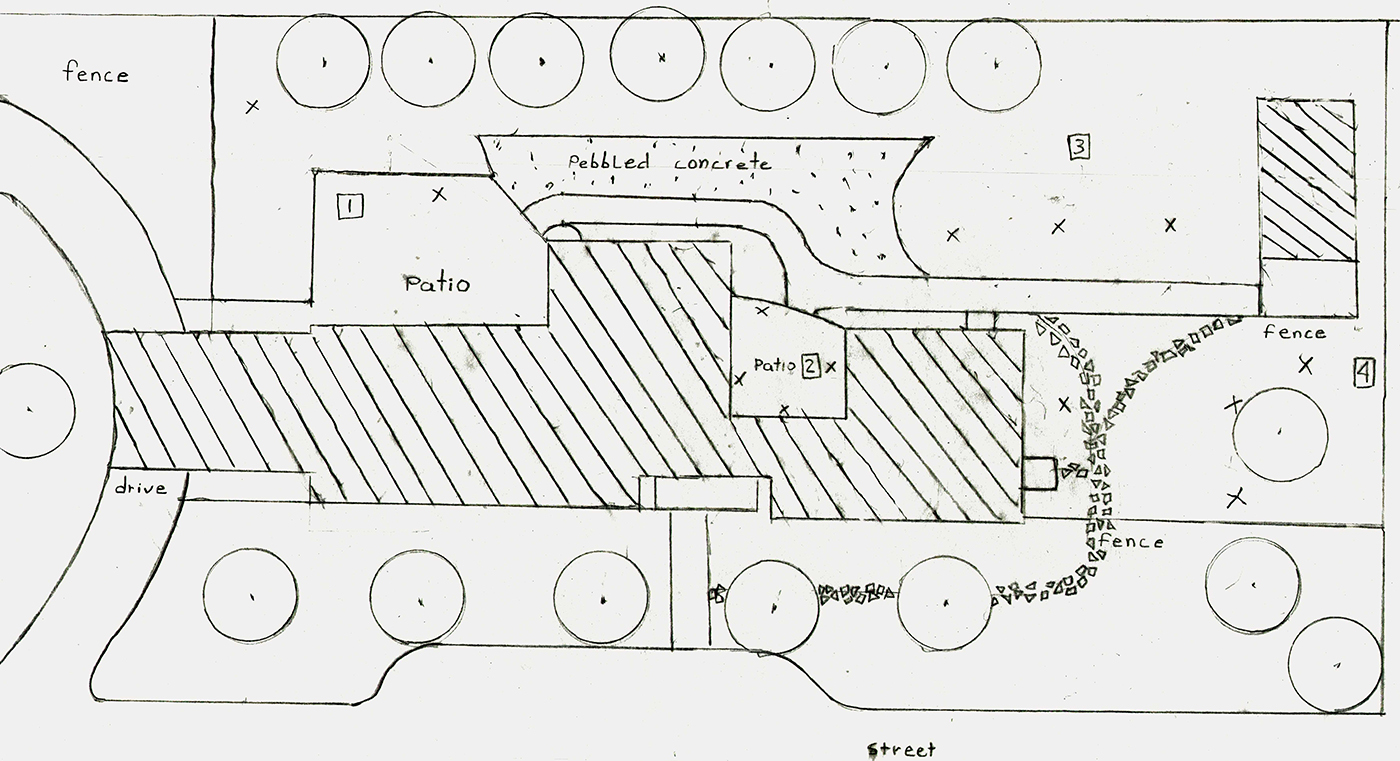

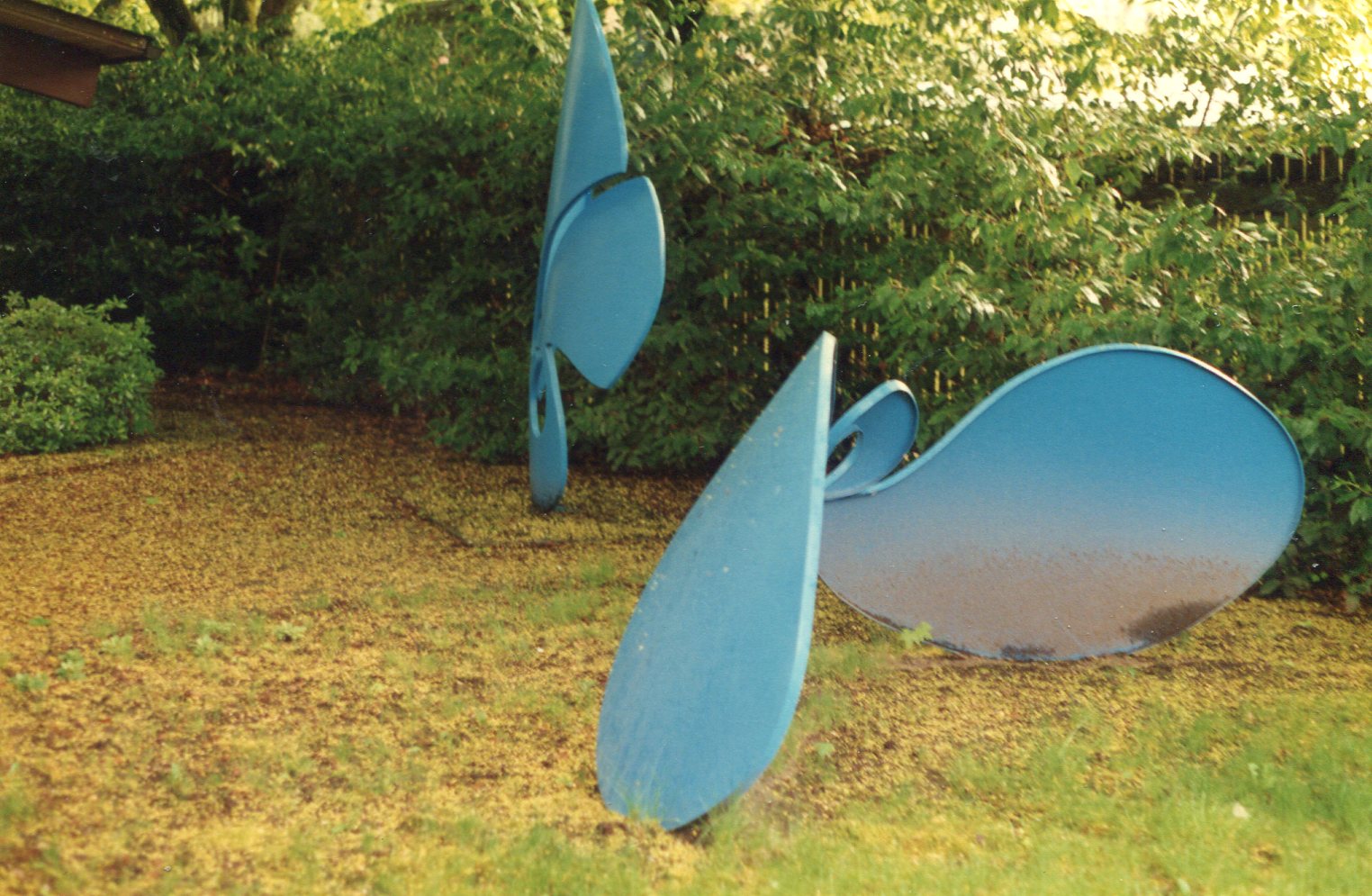

Sculptures aren’t as ubiquitous as paintings. I’ve found that people who are definite about the kinds of paintings they like tend to be more open about sculptures. My intention in posting this website is to make contact with persons who have sculpture gardens, possibly to spark an interest in sculpture in others who haven’t thought about it, and to show friends and acquaintances an activity of mine.

In countless ways, art enters everyone’s life. Paintings and other wall art are the commonest sign of it in homes. One reason is that they don’t take up space, whereas sculptures, especially standing sculptures, can get in the way. Outdoor sculptures don’t have that disadvantage, as many people have found. A private sculpture garden on the grounds of the home – a combination of art, landscape, and exteriors – is an outdoor gallery, analagous to the familiar gallery of pictures inside the home.

Public sculpture gardens and parks have greatly multiplied in recent years, and private sculpture gardens have kept pace. Private sculpture gardens tend to be more personal than public ones, as is to be expected.